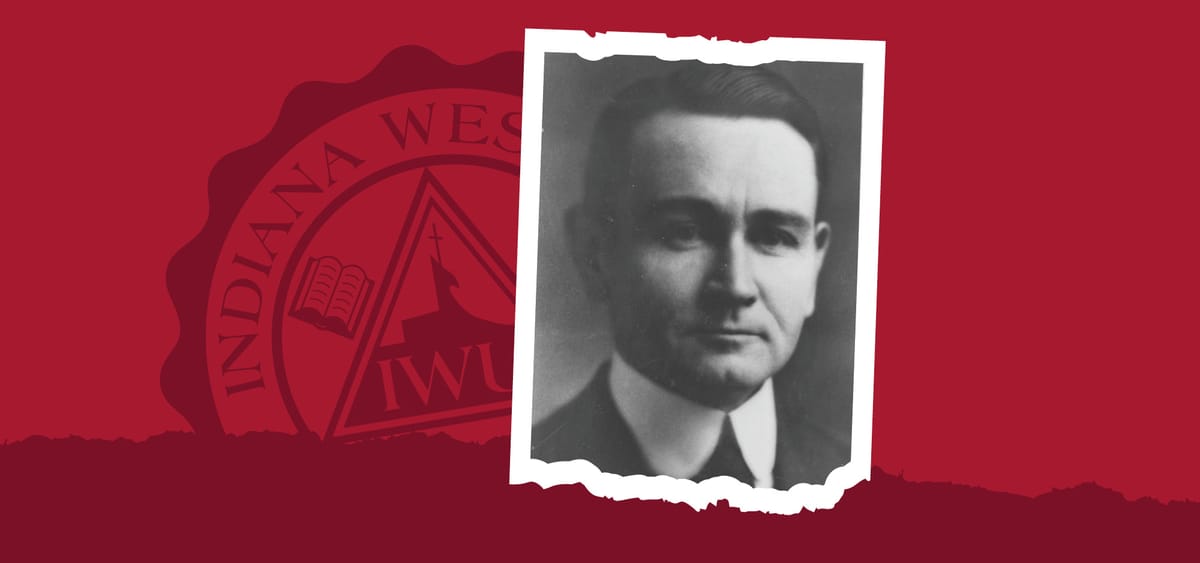

Presidents of the Past—Henry C. Bedford (1919-1922)

The First President

The Indiana Conference of the Wesleyan Church elected Henry Bedford as the first president of its brand-new college in Marion, Indiana on July 2, 1919. At the time, this new institution was still in the planning stages, but when another college put their land and buildings up for sale, a clear path forward began to take shape. Because many of this former institution’s faculty were open to staying in the area, the college already boasted several staff members and state-of-the-art facilities before it was even named. The campus consisted primarily of what was referred to as “the Old Triangle”—a triangular tract of land on which the administration building and some other buildings were located.

About a month after Bedford was hired, the school officially gained a name, becoming known as Marion College. For the first year of his presidency, Bedford helped finalize the planning and construction of the college, ensuring proper placement of everything for its first academic year. Because Marion was used to colleges arriving and departing within just a few years, Bedford and the Wesleyan Church committed to raising Marion College’s chances of success as much as possible prior to its first year. President Bedford also began to build relationships with the city of Marion during this year, helping to assuage fears concerning Marion College’s longevity, given the history of previous institutions.

By the time Marion College opened during the following fall, it consisted of five academic programs—the academy (high school), the college, the music department, the theological department, and the oratorial department. Fall enrollment consisted of 235 students which grew to 280 by spring. Despite just beginning, Marion College claimed its first five graduates at the end of the 1920-1921 school year.

Due to the theological department coming in separately (after previously existing as Fairmount Bible School) there was a level of tension and division between the theology students and others—something Bedford addressed to keep the school from fracturing. During one particularly memorable chapel service, President Bedford blatantly spoke about the issue, advocating for unity and an end to the growing enmity between the two groups. While Marion College was still young and just getting started, Bedford’s hopes were high for its future, saying it stood “ready and anxious at all times to give its aid in community endeavor and wanted to be considered part of it.”

Bedford also believed Marion College fit the definition of the “Ideal College” even this early on, noting it was a college which was free to pursue its mission as an enlightener of mankind, didn’t mistake size for greatness, never sacrificed the bonds of students and faculty, gave comparatively few courses but gave them well, and contained a democratic spirit positively impacting the community.

By the end of its first year, Bedford ran a Marion College full of quality faculty and successful students who all appreciated him. He predicted running the college would cost more than the Indiana Conference of the Wesleyan Church anticipated, but when this proved true there was criticism of him for overspending and paying too high of salaries. Bedford’s growing relationships with community members also sparked criticism, causing accusations of engaging with “worldly elements” too much.

Most crucially, his stance on doctrinal positions was called into question, with some arguing it was simply a semantic difference and others convinced his beliefs were theologically distinct from those of the Wesleyan Church. Bedford’s response to this was to state, “Full salvation as taught in the old Bible is the delight of my heart. Justification by faith in Jesus Christ and the Baptism of the Holy Spirit as an anointing subsequent to a full and complete consecration is my creed. I trust I am not a Wesleyan Methodist because my father has been a minister for fifty years… but because I believe in the… doctrines of the church. There are some notions about ‘Holiness’ which I do not accept but they are minor matters and make no particular difference with our service in God’s cause.”

This situation led to many backers of the school withdrawing their financial support due to frustration with the charges brought against Bedford. Additionally, many people from across the city and throughout the school came to Bedford’s defense, vehemently denying the existence of any genuine issues with Bedford’s beliefs or actions.

Marion College faculty stated, “First, we have found President H. C. Bedford a man of the highest Christian character, manifesting in all things a Christian and spiritual life. Second, we have found him a capable and efficient administrator, with broad vision and high ideas for the institution, and to him we attribute the larger part of the splendid success already achieved by the college. Third, we feel that a continuance of President Bedford’s administration is the most certain and probably the only possible means of assuring that genuine scholarship and true spirituality be maintained at Marion College.”

The Board worked to support Bedford during this time, but in the end Bedford’s departure after his second year was finalized as no satisfactory resolution to concerns was reached. After this was announced, the president once again appealed to the students to “live in harmony” with each other and their new administration. In February, 1922, Bedford announced his replacement by current faculty member John W. Leedy. When Bedford left at the end of the 1921-1922 school year, several faculty and staff members left with him in protest.

Though he only spent three years as president and only served during two academic years, President Henry C. Bedford managed to leave an indelible impression on Marion College. Thanks to his efforts, the school was able to start well, establishing itself in a city justifiably suspicious of new colleges, and managing to not only help bring in almost 300 students, but actively working to increase unity between them as much as possible. While the nature of his departure was highly unfortunate, it is nonetheless true Bedford was invaluable during his time as president, and without him the Indiana Wesleyan University of the present might not exist.

Want to read more? Check out the other articles in the "President's of the Past" series!

- Henry C. Bedford (1919-1922)

- John W. Leedy (1922-1927)

- The Forgotten Presidents (1927-1932)

- William F. McConn (1932-1960)

- Woodrow I. Goodman (1960-1976)

- Robert R. Luckey (1976-1984, 1986-1987)

- James P. Hill Jr. (1984-1986)

- James B. Barnes (1987-2006)

- Henry L. Smith (2006-2013)

- David W. Wright (2013-2022)