Celebrations and Lamentations

Rooted in abolitionist conviction, the Wesleyan Church has a rich and evolving history with race. From its founding to the present day at IWU, this legacy reveals a deep connection to justice, perseverance, and a continued commitment to racial reconciliation.

The Wesleyan Church sprang directly out of the abolitionist movement, made significant contributions to the fight to end slavery, and then had numerous missteps over the course of the twentieth century (missteps which IWU is not exempt from), before eventually arriving at the current moment, wherein the Wesleyan Church is arguably on an upward trajectory.

The history of the Wesleyan Church is one which is inexorably tied to the history of racial issues in America. This is not to say the Wesleyan Church has always done the best job of approaching racial issues - indeed, this piece shall go on to show many of the ways in which it has failed to do as much good as it could have - but there is value in celebrating both the many triumphs of the Wesleyan Church and also in lamenting and repenting from the failures of its members. Indeed, if we are to truly love and serve God to the fullest extent of our ability, both are arguably essential and necessary. As we make our way through Black History Month, it is worth considering the ways in which our denomination's origins are explicitly connected to the fight for racial equality.

Antislavery Foundations

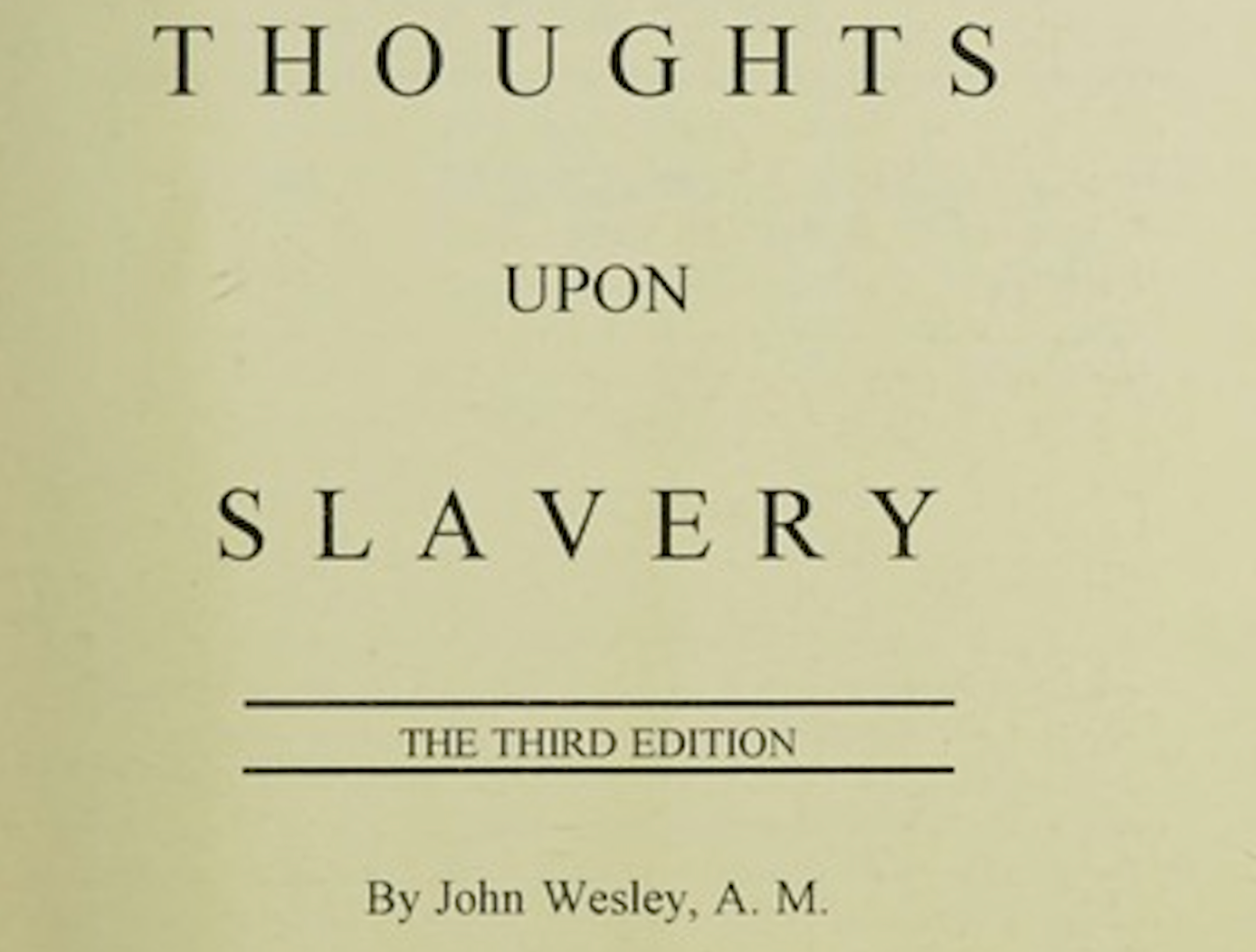

In 1774, John Wesley published his book Thoughts Upon Slavery wherein he clearly wrote against the evils of slavery, particularly as it existed in England. Wesley was so outspoken against it he even preached antislavery sermons within Bristol - one of the hubs of England’s slave trade. Indeed, in the last letter he ever wrote, Wesley referred to slavery as “that execrable villainy which is the scandal of religion, of England, and of human nature… Go on, in the name of God and in the power of his might, till even American slavery (the vilest that ever saw the sun) shall vanish away before it.”

It should come as no surprise, then, that when the Methodist Episcopal Church was founded, its guidelines included a rule against the selling or purchasing of any human being and required any slave-holding Methodists to free them within the year. While there were laws which kept this from being enforceable within the south, the point was still meant to be clear.

Methodist Regression - Slavery Continued

Unfortunately, there was immediate resistance to this stance and within just six months the Methodist Church had walked this back. While still condemning it through their words, Methodism would no longer do anything to ban or oppose it. By 1804 the Methodist Episcopal Church was issuing two separate versions of their guidelines - one version condemning slavery, and a second version intended for the south which did not include any anti-slavery statements. While still working to evangelize to slaves and indentured servants, the Methodist Episcopal Church no longer sought to free them. Indeed, slaveholders were commonly found in the denomination and were treated no differently from anyone else, the fact they owned slaves going uncriticized. By 1828, it became abundantly clear Methodist leaders would do nothing to take action against those within the denomination who not only kept but abused their slaves. While the official stance might have still decried slavery, the actual posture was far less opposed to it. Within just sixty years, Wesley’s utter abhorrence of slavery had slowly been replaced by blatant acceptance of it within the very group of people who claimed to follow in his footsteps.

Change Begins

While many topics were discussed during the 1836 General Conference, the most notable in hindsight was minister Orange Scott’s speech against the evils of slavery. The response he got was his removal from the relatively large church he pastored and reassignment to a tiny church in Massachusetts. Ironically, while this had been intended as a punishment, Scott proceeded to grow the congregation of his new church drastically, fostering spiritual revival in a community which otherwise might not have experienced it.

This failed punishment did not deter Scott whatsoever, and in 1840 he once again spoke out against the evils of slavery at the General Conference. Once again he was shut down, his already shaky reputation only decreasing, but the message was at least clear - Orange Scott was not a man to give up easily, and the abolitionist cause was one he was willing to fight for no matter what the consequences might be.

For two more years Scott existed within the Methodist Episcopal Church, trying to cause change and push the church back towards the original views of both Wesley and the denomination itself, but to no avail. Eventually, in late 1842, Orange Scott and four other ministers formally left the Methodist Episcopal Church. The other ministers consisted of LaRoy Sunderland, editor of the antislavery paper Zion’s Watchman; Lucius Matlack, who was denied ordination within the Methodist denomination twice due to his abolitionist views before being taken in by Orange Scott who ordained him at his church in Massachusetts; Jotham Horton who pastored several churches; and Luther Lee, a prominent and well-respected pastor who had become an abolitionist in 1837 after another pastor had been killed for his abolitionist sermons.

The Birth of the Wesleyan Church

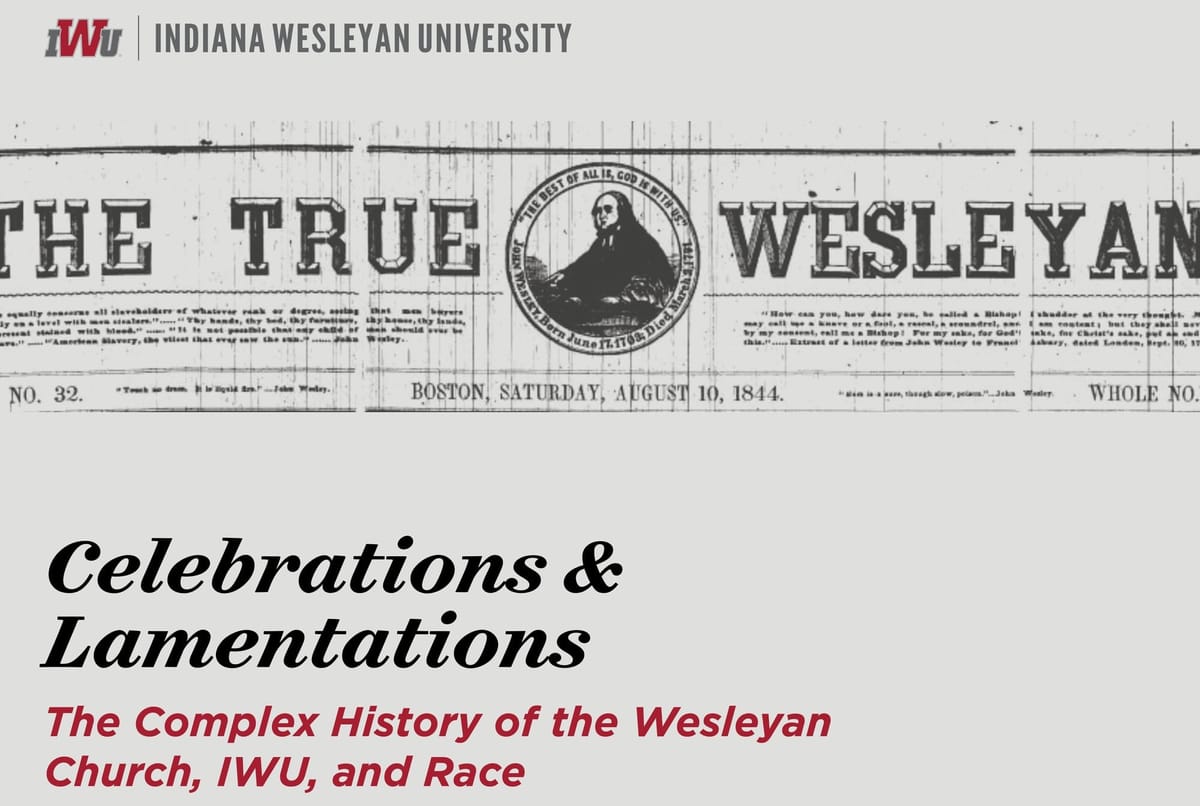

Having left the Methodist Episcopal Church together, they decided to continue onwards together, starting to publish a paper in January 1843 called The True Wesleyan. Several other churches had begun separating from the Methodist Episcopal Church over the course of the past few years - partially due to the issue of slavery but also partially for other reasons, such as disagreements over the role of bishops within the church. Additionally, it is worth noting that unfortunately not even everyone who split from the Methodist Episcopal Church over the issue of slavery did so because they believed in equality - a portion of them simply felt slavery denigrated labor itself. While it is important to note none of the major individuals who split from the Methodist Episcopal Church were in this group, as they all did genuinely care about the souls of those enslaved, a portion of these individuals did exist, only serving to complicate matters further.

Recognizing that the number of churches splitting away from the Methodist Episcopal Church was only continuing to grow, Orange Scott and his associates called for a meeting of as many of these churches as possible, in the second issue of The True Wesleyan.

Just a few weeks later, on February 1st, nine pastors and forty-three members of various churches answered The True Wesleyan’s call to gather together in Andover, Massachusetts for the first Wesleyan Antislavery Convention. The meeting was successful enough that a second meeting was held on the 31st of May to organize them all into a connected group.

Over the next few years their group continued to grow, with the meetings becoming daily and needing to move into a new space as more than two thousand people began to attend. By this point the organization had grown to about six thousand people total.

Given they were reaching a considerable size, it was decided they needed a convention president - Orange Scott unsurprisingly being chosen - and the core values of the burgeoning denomination were created, with Luther Lee writing both the denomination’s first history and first systematic theology. They gave themselves the official name of the Wesleyan Methodist Connection of America. This name was partially chosen because Luther Lee argued the word “church” was best reserved for local bodies and the word “connection” was in fact a more accurate representation of what this new denomination was.

Less than a year-and-a-half later the Wesleyan Methodist Connection had grown from six thousand members to well over fourteen thousand.

First Losses

Not long after, the newly formed Wesleyan Methodist Connection suffered its first loss as founding leader LaRoy Sunderland left the denomination due to its stance against secret societies. Over the following years, Sunderland eventually decided to leave Christianity entirely. While this certainly came as a blow to the Wesleyan Methodist Connection, particularly to those leaders who had known and worked with Sunderland for several years at this point, it was not as devastating as what would soon follow. On July 31st, 1847, Orange Scott passed away due to a lengthy battle with tuberculosis. Luther Lee preached the sermon at Scott’s funeral, extolling both God and the ways in which he had used Orange Scott - Lee’s associate, brother in Christ, and friend.

A few years later, in 1851, the Southern conferences withdrew from the Methodist Episcopal Church. Seeing this as essentially a sizable enough change in the makeup of the denomination and seeing the Wesleyan Methodist Connection as a purely temporary organization, cofounder Jotham Horton left the Connection to return to the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Southern Expansion

Although the Wesleyan Methodist Connection had suffered the loss of three of its founding members, this was not an entirely negative time by any means, as there were advances being made by the church. The same year Orange Scott died, pastor Adam Crooks established the first Wesleyan church in the south, named Freedom’s Hill. Over the course of the next two years, eight additional Wesleyan churches were founded in North Carolina and Virginia. By 1851, there were over five hundred Wesleyans in the area, a sizable achievement given the denomination’s continued outspoken abolitionist stance. Adam Crooks was thrown in jail for his antislavery statements and beaten up on multiple occasions, but even these events did not discourage him, as he famously called for all Wesleyans to be willing to lay down their lives for God’s truth if needed. Crooks would not stop until all enslaved people were free.

Risking Everything for Christ

While the opposition Adam Crooks faced was quite bad, it was not isolated, unfortunately. In North Carolina, Wesleyans were prohibited from speaking on public property by the law. Additionally, when the Fugitive Slave Law was passed, everyone was required to return escaped slaves regardless of the legality of slavery within their own state. In opposition to this law, the Wesleyan Methodists announced in The True Wesleyan they would disregard it entirely due to its blatantly unbiblical nature. Luther Lee stated, “I never would obey it… If the authorities wanted anything of me, my residence was at 39 Onondaga Street.” This was an especially bold stance for Lee to take as he personally assisted dozens of escaped slaves in getting to freedom every month during his years as a pastor in Syracuse, New York. Even so, Lee was not afraid to boldly stand for what he knew was right.

Luther Lee was far from the only Wesleyan participating in the Underground Railroad, however. Adam Crooks and his church, Freedom’s Hill, were also engaged in it, as was Laura Smith Haviland, who opened and operated the first ever Underground Railroad station in Michigan out of her own house, in addition to the instances when she would personally lead escaped slaves to freedom.

Pastor Daniel Worth was also arrested in December of 1859 and locked in prison due to having distributed antislavery literature. Worth was left in the unheated cell for the duration of the winter and suffered permanent disability, after which he spent a year in prison - even so, he too continued on unabated. When the Civil War began, Wesleyans were given new opportunities to quite literally fight for what they believed in, with cofounder Lucius Matlack entering as a chaplain, before later serving as a colonel in the field, and later still as a provost marshal. Throughout the Civil War, Adam Crooks' declaration that they be willing to lay down their lives for the cause was put to test innumerable times.

After the War

While the outcome of the Civil War was largely a positive one - the abolitionist movement having finally achieved its goal in the most major of ways - the one downside to this was that the Wesleyan Methodist Connection was now left with something of an existential crisis. While some had viewed the organization as a permanent group, many still viewed it as temporary and this difference in perspectives quickly became an unintended problem. Many churches now felt the group’s purpose had been concluded and that it was no longer needed - including cofounders Luther Lee and Lucius Matlack themselves, who had both returned to the Methodist Episcopal Church not long after the Civil War, seeking to be reunited with the churches which the Connection had originally sprung from.

The Wesleyan Methodists thus found themselves in a rather difficult situation in 1867, due to the fact none of their original founders were left. After much deliberation over his own stance on whether the Wesleyan Methodists should continue on or return to the Methodist Episcopal Church fully, Adam Crooks came forward as the new leader of the denomination. Many of President Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction policies were still sizable issues - such as the Black Codes, which kept African Americans from voting in Southern states - and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan made it clear that while laws had changed, many hearts had not. As such, it became evident there was still a significant problem in the United States’ treatment of racial issues, meaning the denomination’s work wasn’t done. Additionally, there were other issues - such as the roles of bishops and stances on secret societies - which created smaller but noticeable differences between Wesleyan Methodists and the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Wesleyan Regression

Unfortunately, while Adam Crooks and his fellow Wesleyans might have been zealous about defending truth and their fellow man, those who followed proved less caring. By the time Crooks died in 1874, everything still seemed relatively on track - indeed, the concept of segregating churches was blatantly disregarded nine years later when suggested. In 1907, however, the first cracks began to occur. Although various explanations and excuses were offered, there was truly no way to justify the segregated conferences which were being held. Some of the black members of the Wesleyan Church were vocally supportive of it - stating they didn’t want their churches to be integrated with those of white Wesleyans - but even under this justification the issues of division were still being allowed to persist unopposed. Over the course of the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth, the Wesleyan Church became increasingly passive regarding social reforms, as what Robert Black and Keith Drury refer to as “the Great Reversal” occurred.

Over the course of less than a century, the Wesleyan Church had repeated the story of the Methodist Episcopal Church, going from initially very zealous in their opposition to racial discrimination, to becoming apathetic and passive. While platitudes persisted regarding racial equality, action had sadly ceased.

IWU and the Twentieth Century

One thing which is worth noting and celebrating during this period is the fact Indiana Wesleyan University was never at any point racially exclusive or segregated. Individuals such as Lewis A. Jackson and Nevada Pate were not only perfectly welcome and appreciated, but have since continued to be celebrated for their accomplishments.

It is also worth noting that in 1955 and 1964, the Wesleyan Church explicitly stated they were supportive of civil rights, even going so far as to admit the failures of the past several decades. Unfortunately, however, while this support certainly has value, there was still very little action being taken - certainly nothing approaching the actions of even one of the denomination’s founders. While the gospel message and evangelism were still very much important to the denomination during this time, the ease with which many could go about their lives ignoring the issue unfortunately led to a disappointing lack of action.

Sadly there were even elements of Indiana Wesleyan University’s history in this regard which were negative, because while the university has always been open to students of any nationalities, the 1960s saw the student handbook institute a ban on interracial dating which lasted into the 1980s.

Indeed, it was not until the mid-to-late 1980s when the Wesleyan Church finally reversed the problems which it had allowed to persist through complacency. By the end of the 1980s, all churches which had been segregated within the denomination were integrated. While some black Wesleyans had chosen to segregate for many decades, this was finally seen as still allowing issues to persist rather than ending them. Additionally, the interracial dating ban at IWU was finally removed from the handbook.

Where We Are Now

In some ways it is hard to believe the aforementioned issues only ended forty years ago and yet when we look at the current state of the Wesleyan denomination, and Indiana Wesleyan University specifically, there is some solace to be found in the fact things have drastically improved, showing a turn back towards the positive foundations of the denomination. The fact there is still potential for growth should also be noted, but the improvements have certainly been substantial.

Indeed, at IWU we now have several groups specifically dedicated to highlighting other cultures - such as the Black Student Union and the Luther Lee Scholars, the latter of which also includes scholarship opportunities while paying tribute to one of the denomination’s founders. Additionally, efforts to highlight racially inclusive holidays and celebrations, lift up diverse student organizations, and emphasize diversity in a way which is both clearly evident and personal for students further show that while IWU still might not be perfect, it is still working to become increasingly better and take every opportunity to continue working in the areas where it's strongest while growing in the areas where it's weaker.

When looking back over our history, there is indeed much to celebrate and much to lament - both for our denomination as a whole and our university specifically - and while it would be incredibly easy to simply emphasize the positives and forget the negatives, there is no better way to repeat the mistakes of the past than to ignore them. As such, it is incredibly important for us to remember and keep in mind both sides of our history so we can make our future the best it possibly can be.

Sources

"Antislavery Roots". The Wesleyan Church, July 29 2013. https://www.wesleyan.org/antislavery-roots

Black, Robert and Keith Drury. The Story of the Wesleyan Church. Wesleyan Publishing House, 2012, pp. 24-77, 92-93, 132-134, 191-192, 254.

Hawkins, Rusty. Personal communication. January 19, 2024.

"Our Story." The Wesleyan Church. https://www.wesleyan.org/about/our-story